Legacies produce all places. As a historian, I am perhaps more sensitive to that than most. I see multiple pasts, multiple narratives everywhere I turn, stretching from the immediate present back through years, decades, even millennia. The evidence is all around us if we  bother to look and listen. Yet, reconciling the successive, overlapping, or competing pasts in one place can confound the historically inclined. It did me on a visit to the University of Victoria.

bother to look and listen. Yet, reconciling the successive, overlapping, or competing pasts in one place can confound the historically inclined. It did me on a visit to the University of Victoria.

As an American visiting the university campus, I could not help but be struck by the indigenous presence–a presence most colleges in the states ignore, deny, or remain indifferent to. Not so at UVic. Totem poles grace the commons. A First Peoples House occupies a central position on the main mall at the center of campus. And Native artistic themes rival

As an American visiting the university campus, I could not help but be struck by the indigenous presence–a presence most colleges in the states ignore, deny, or remain indifferent to. Not so at UVic. Totem poles grace the commons. A First Peoples House occupies a central position on the main mall at the center of campus. And Native artistic themes rival regal crests as dominant motifs. Of course, all universities in the Americas rest on Native land, but UVic acknowledges it like few others.

regal crests as dominant motifs. Of course, all universities in the Americas rest on Native land, but UVic acknowledges it like few others.

I know that when you walk the very ground of the University of Victoria, you travel across one of the few places where the British in nineteenth-century British Columbia entered into treaties with the First Nations. On February 7, 1852, the Saanich Tribe, or Tsawout and Tsartlip First Nations, surrendered their claims for 41 pounds, 13 shillings, and 4 pence. At least according to British authorities. First Nations people dispute the agreements. Contention over these legal legacies, however, are not publicized widely alongside the cedar poles that tower over the university’s commons spaces today. I suppose it is “easier” that way.

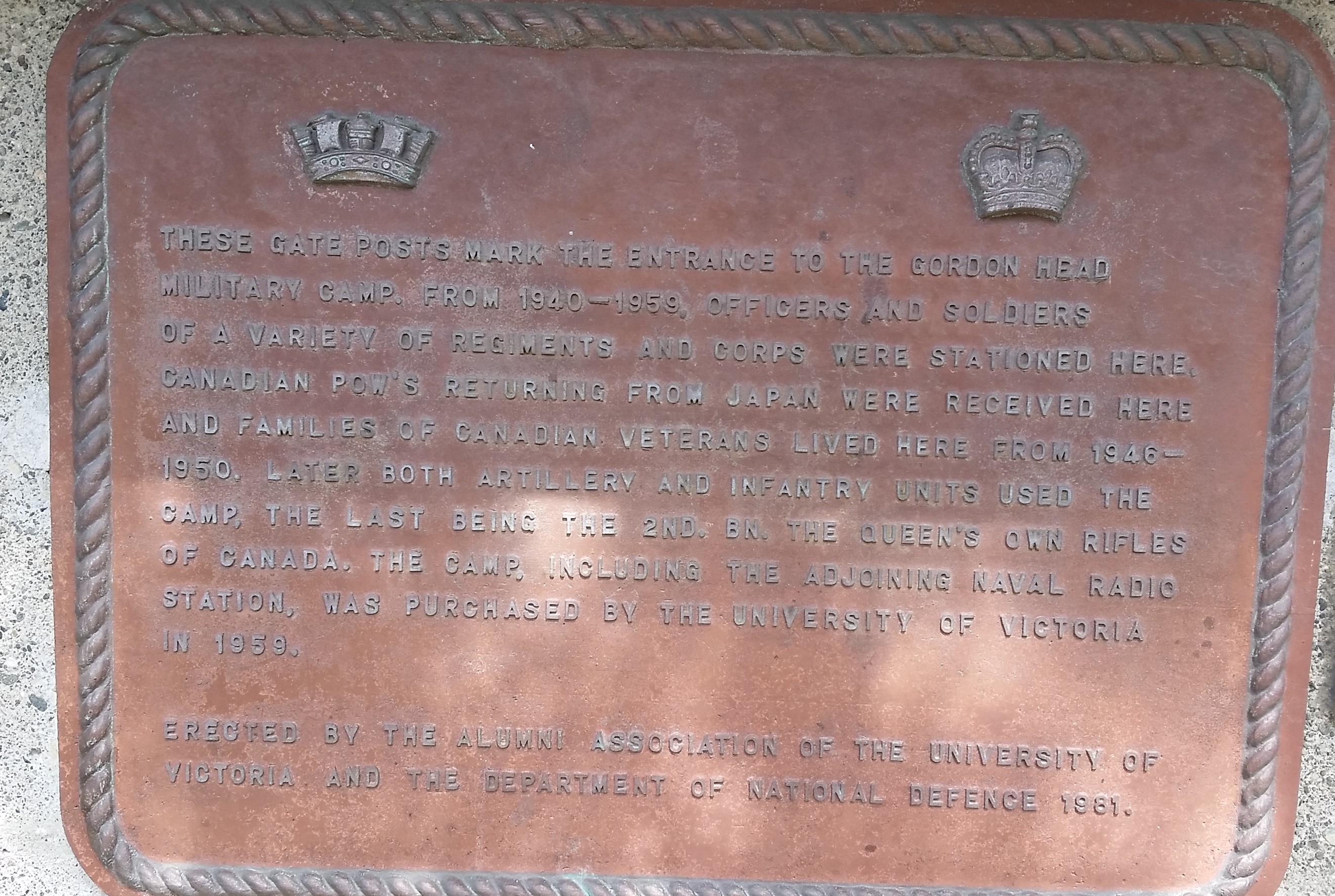

Other histories mingle here but without as many prompts confronting me as I walked along today’s pathways. Hidden or muted is the campus’ legacy as a military camp, a historical antecedent I did not realize and is easy to overlook. During World War II, the Canadian naval services operated a Special Wireless Station in the Gordon Head neighborhood, listening in on the Pacific Theater. POWs returned here. Veterans’ families lived here. It closed before 1960.

The Canadian armed forces hardly brings to mind rampant militarism and World War II largely retains its status as “the good war” fought by “the greatest generation.” Still, I wonder if it is worth remembering that you cannot have militarism without a military. And how does this history layer on or intermingle with the indigenous presence here? And why do I find this ambiguity uncomfortable?

By the postwar era, Victoria College grew into a university and relocated to the former listening station’s grounds. And if you know where to look, military legacies remain. Guard posts innocuously hold commemorative plaques I’d wager few have stopped to read. Huts, scattered across campus, are the unmistakable architectural artifacts.

Huts, scattered across campus, are the unmistakable architectural artifacts.

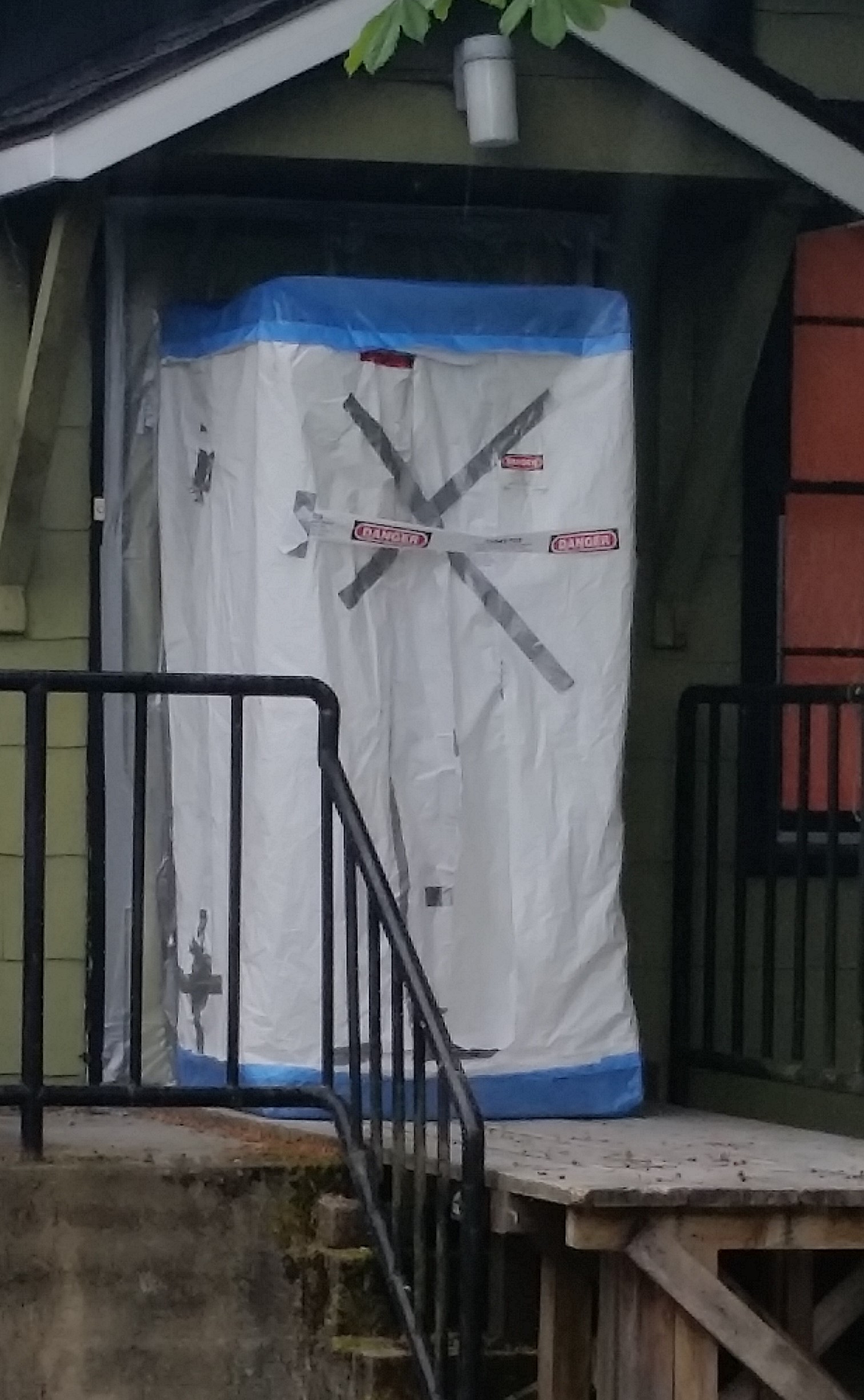

Low, long, green and plain, E Hut now fittingly houses Campus Security. As I walked around the building on a rainy morning in June, other legacies appear. The front door is locked, a Danger sign warning off all but “authorized personnel.” Peering past this prohibition, I see the reason: asbestos removal. Around back, a vertical rectangular space, enclosed by ratty

Low, long, green and plain, E Hut now fittingly houses Campus Security. As I walked around the building on a rainy morning in June, other legacies appear. The front door is locked, a Danger sign warning off all but “authorized personnel.” Peering past this prohibition, I see the reason: asbestos removal. Around back, a vertical rectangular space, enclosed by ratty  plastic patched by duct tape and resembling a standup shower, offers deterrence but can hardly be substantial security. What’s this say?: A war-era building finally extracting its poisonous fibers to prevent (further?) ill health. Institutions, like schools, it seems, have a long history of being deadly to those who live and work there. Ask the indigenous community about residential schools, if you don’t believe me.

plastic patched by duct tape and resembling a standup shower, offers deterrence but can hardly be substantial security. What’s this say?: A war-era building finally extracting its poisonous fibers to prevent (further?) ill health. Institutions, like schools, it seems, have a long history of being deadly to those who live and work there. Ask the indigenous community about residential schools, if you don’t believe me.

Just 200 meters from E Hut, next to a bus loop and the university bookstor e and a cinema sign ironically advertising “Where to Invade Next,” stands a Coast Salish housepost. Surrounded by a native plant garden–even the plants are indigenous at UVic–the post stands silent in the shade, off to the side.

e and a cinema sign ironically advertising “Where to Invade Next,” stands a Coast Salish housepost. Surrounded by a native plant garden–even the plants are indigenous at UVic–the post stands silent in the shade, off to the side.  Called “Empowerment” and created by artist Butch Dick, this post acknowledges both tradition and a hope for the future. In other words, like all of us, in all places, times, and cultures, it is lodged in the present–an accumulation of the past and all its detritus and poised for the future yet unwritten.

Called “Empowerment” and created by artist Butch Dick, this post acknowledges both tradition and a hope for the future. In other words, like all of us, in all places, times, and cultures, it is lodged in the present–an accumulation of the past and all its detritus and poised for the future yet unwritten.

Alongside the First Peoples House, a tent covers a totem pole in-progress. The cedar smell punctures the air as rain drops onto the protective tarp. Art like this–public, indigenous,  striking–serves powerful purposes for this place. It obviously reflects the university’s efforts today to create a stronger indigenous presence and improve opportunities for First Nations student success. But there is more here, I think.

striking–serves powerful purposes for this place. It obviously reflects the university’s efforts today to create a stronger indigenous presence and improve opportunities for First Nations student success. But there is more here, I think.

This emerging-totem calls to mind occupations and legacies. The layerings here are rich, if incongruous. Indigenous land colonized by British colonial and commercial powers to be reoccupied by soldiers almost a century later, symbolically and effectively interweaving the economic and military power that dispossessed Indigenous people in the aftermath of European colonization. And now First Nations presence pointedly asserts itself, demanding attention and understanding and recognition. I stop for a moment and consider these juxtapositions: Indigenous land. Colonial farms. Military installation. Institution of higher learning. And I ask: Can this be a place for reconciliation? I wonder, worry, and then hope.

Most of all, I walk off thinking. This place has done its work. The past and its multiplicities bubbled up without resolution, just as the creatures being carved are still emerging, still indistinct, still being made. As are all places and times and beings.