The Last Wilderness Endures

Murray Morgan from the edge of the continent

The Continent's Edge

In April 1955, Saturday Evening Post published a story from the edge of America.

Famed Northwest journalist Murray Morgan reported from Destruction Island off Washington’s coast. A small group from the Coast Guard staffed the lighthouse there at the “most remote and forlorn spot in the United States.”

As he did with all his subjects, Morgan captured the people and place well, bringing to the magazine’s readers a palpable sense of what isolated living on Destruction Island must have felt like.

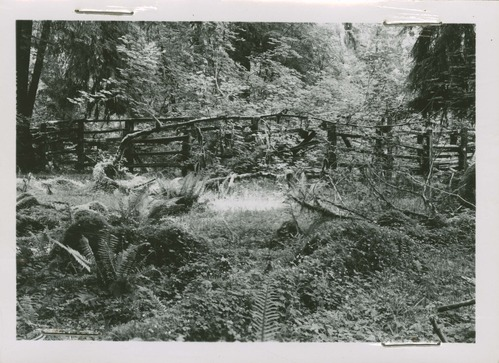

When Morgan left the island, rain beat down as it so often does on the Northwest coast. Due east from Destruction was a coastal strip of Olympic National Park (as written about last week). He watched the coast grow closer. The coastline had remained wild and forested because the “wind-tortured” trees beaten by decades of constant weather did not appeal to loggers who could find huge, straight trees more suitable for making lumber a little inland.

By being worthless, the coastal forest’s beauty was protected.

But Morgan questioned that logic.

Can beauty be worthless?

He thought:

This is the last bit of the country, the farthest reach. It looks now as it did when Captain Gray saw it. It is unchanged since Lewis and Clark started west. It is the last wilderness, and will remain so. And I was glad.

Morgan’s excursion to Destruction Island and his sentiment about the continent’s last wilderness encapsulated his perspective on the Olympic Peninsula so well that he ended his book, The Last Wilderness, with this chapter drawn from his Destruction Island reporting.

The Last Wilderness

Viking published The Last Wilderness the same year Morgan’s Saturday Evening Post article appeared. He had published Skid Road: An Informal Portrait of Seattle with Viking a few years before to some acclaim. Famed critic, editor, and writer Malcolm Cowley encouraged Morgan when he visited the Northwest and championed both books for Viking.

My guess is Skid Road is the most-read book of Seattle history, if not all of Pacific Northwest history. The Last Wilderness feels like a rural companion to Skid Road, a series of chapter profiles of people and place.

Morgan described peninsula towns developed for US customs collection or for lumber production. He portrayed towns that dreamed — of a transcontinental railroad terminus or of a utopia where anarchism (and sometimes nudism) was practiced. He depicted communities of violence (against people and nature) and places of reverence.

The point, always, was to illustrate how the character of place seeped into the character of the people, and vice versa. Morgan’s career as a Northwest writer and historian drove that home again and again. Perhaps nowhere is it as clear as in The Last Wilderness — maybe because of the very extremity of the peninsula itself.

A Craftsman at Work

Three things make The Last Wilderness work.

First, Morgan knew the peninsula firsthand. In his Foreword/Preface (I have two editions and they use different titles for this opening section), he explained how his “first memories of childhood are vacations spent on the Olympic Peninsula.” He described standing in a river while salmon spawned and looking across the water to see logs shooting off cliffs to water where they’d be transported to mills.

“I have been in love with the Olympics for as long as I can remember,” he confessed.

After graduating from the University of Washington, Morgan headed to Hoquiam to work as a reporter, a place he left and returned to for work and recreation throughout his years. Nothing can replace knowing a place where you’ve worked and walked and played.

Second, Morgan knew both the history and the present. Again, as in most of his work, he zipped in and out of his roles as historian and reporter seamlessly. He filled the book with quotations from 18th-century explorers, 19th-century newspapers, and 20th-century conversations. He knew how to research in archives and report on the ground. And credit is also due to his wife Rosa who was an important research collaborator and editor who “battled valiantly against some extravagances [Morgan] had thought to include.”

Knowing the evidence, past and present, and marshalling it into a story is far harder than it appears on the printed page. Morgan struck the balance consistently, page to page, book to book, decade to decade.

Third, Morgan could write. You’ll need to dig into a Morgan text to appreciate how often he turns a phrase just right, how frequently he captures the weight of a character perfectly, how consistently he frames an issue in a memorable way.

Consider how he described the rain:

On the fourth day of the hunt it began to rain, a real Hoh Valley rain with weight behind it. The sort of rain where the sky leans on the back of your neck.

Read how he characterized timber-thinking once pulpwood found a use:

Lumbermen no longer think of a tree as something to be cut up into squares of lumber, but rather as a bundle of fibers, wrapped in bark, to be taken apart and put back together again in many different forms. A forest can be stretched farther that way.

Note how he personalized the abstraction of seeds collected for planting:

For a moment I will never forget, I stood in the dim office, with the rain beating on the roof, and I held in my hands the seed of two million Douglas firs — the forest that our children’s children’s children will see growing on the slopes of the Olympics.

These all are words that stick with you, like pitch to your fingers. After 100 or 300 pages of this prose, you feel the dampness of the Olympics on the pages of The Last Wilderness.

That’s the result of a craftsman working hard.

A Parting Shot

The “wilderness,” especially the last one, necessarily brings to mind transitions. Like a frontier that closes, a wilderness that’s the last one, points to something ending.

That idea prompts nostalgia, a longing for something gone — the wildness of the Olympic Peninsula or the style of Murray Morgan.

But Morgan recognized the error in relegating all that is good to the past.

He recalled an early assignment as a Hoquiam reporter, covering a Pioneer Picnic where an old-timer proclaimed the heroism of the pioneer, lamenting that “this veritable breed has perished from the face of the earth.”

Not true, thought Morgan.

“There are roads and electric lights on the peninsula now, and some toilets flush, but it remains a wild and lonely place and as such exerts an odd attraction for the self-sufficient and the eccentric, two strains of the veritable breed,” he wrote.

The Olympic Peninsula is a special place, and Murray Morgan is a special writer. Neither is simply a relic of the past to be mourned for having passed but something veritable — that is, something true, genuine — to be embraced and inspired by.

In Other Words

- My friend and fellow Pacific Northwest writer, David B. Williams, is publishing his book this week: Wild in Seattle; Stories at the Crossroads of People and Nature. This includes a collection of his most interesting newsletter pieces about the Seattle area. Have a look at his book page. (If you are a paid subscriber to Taking Bearings, you can read my interview with David here.)

Comments ()