Supporting Agriculture

How the federal government seeded a network for farmers

As Americans are finding out, the federal government is involved in all sorts of things. We often see it as a pesky force of regulation that tells various industries what they can and can’t do and penalizing them for violating rules. But governments also cooperate and invest in research and programs often designed to support those same industries.

In the areas I write about most often — natural resources and agriculture — this tradition of federal investment is old. And while those investments have not always benefited everyone or the land, they are worth understanding if only to recognize that carrots of investment that have accompanied the sticks of restrictions.

Centering Agricultural Education

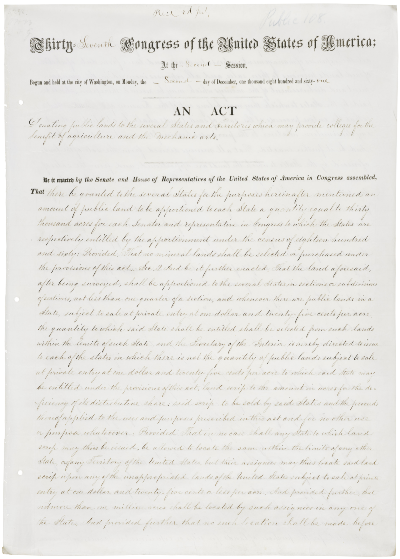

The most symbolic foundation for this kind of government influence might be the Morrill Act (1862). Signed by President Abraham Lincoln during the Civil War, the Morrill Act donated public land to states, which could then sell or manage the lands to support universities, what we call land-grant universities.

In the 19th century, the federal government often felt like it was easy to give away land to states, corporations, or individuals.

Of course, the land the national government was giving away was being taken from Indigenous nations. A serious reckoning of this land grab can be found at Land Grab Universities, an investigative project begun with High Country News but that continues at Grist with an exceptional team of researchers and writers.

In 1890, a Second Morrill Act passed to create Historically Black Land-Grant Universities.

The Morrill Act envisioned land-grant universities emphasizing “such branches of learning as are related to agriculture and the mechanic arts . . . in order to promote the liberal and practical education of the industrial classes in the several pursuits and professions in life.” This reformist ideal, always incomplete and rooted in Native dispossession, laid down a foundation for other, more specific programs.

About six weeks before he authorized the Morrill Act, President Lincoln signed a law created the Department of Agriculture (and a few days later enabled the Homestead Act). The USDA aimed to be useful to American farmers, but given the nature of American federalism, the department and its related activities had to involve the states.

Land-grant institutions embodied that state-federal link. According to a classic study, Science in the Federal Government by A. Hunter Dupree, each college became “a nucleus of the advocates of science in agriculture.”

Growing Agricultural Research

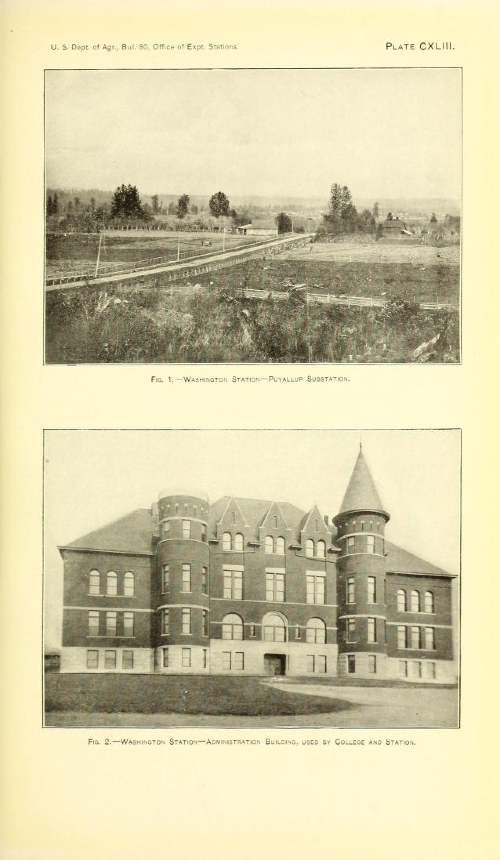

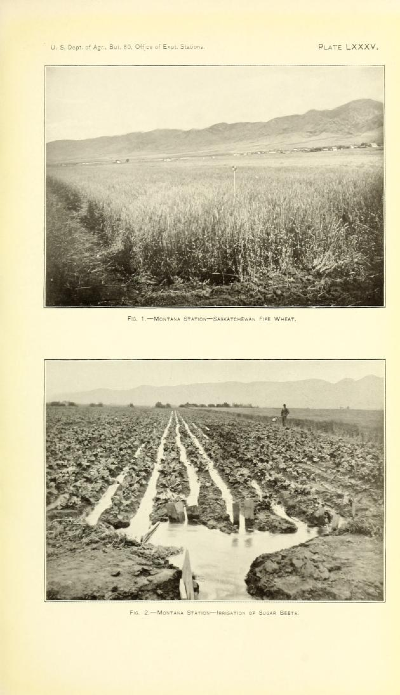

To deepen the commitment to science, Congress passed the Hatch Act in 1887. This law established agricultural experiment stations associated with land-grant colleges. This program allowed research into problems and opportunities specific to local agriculture, recognizing that cotton farmers in Alabama and orchardists in Washington faced different conditions. The act turned the USDA “into a nexus of a system of semi-autonomous research institutions permanently established in every state,” wrote Dupree.

Especially before agribusiness grew so large and could exercise its own dominance, government programs were the only way to effectively conduct and convey research at large scales. It was a singular force. “By 1916 no other great economic interest in the United States could boast such a research establishment for the application of science either in or out of the government,” claimed Dupree.

The research conducted at these stations across the nation fueled research into practical agricultural problems in a decentralized way but with some centralized funding. It required local-national cooperation, although as historian Jeremy Vetter has noted in Field Life: Science in the American West during the Railroad Era, many local researchers bristled at the USDA being insolent and insidious in its insistence at being involved.

Which is to say: local resistance to national initiatives has a long history.

Spreading the Word

From the start, attention was paid to sharing the information widely. The Hatch Act required that “bulletins or reports of progress shall be published at said stations at least once in three months, one copy of which shall be sent to each newspaper in the States or Territories” where the experiment station was located.

Public research funds meant public research results. But that was insufficient.

To get this information into more farmers’ hands, Congress passed a final piece of agricultural legislation in this formative era, the Smith-Lever Act of 1914. In 1912, New York set up a system for each county to have an agriculture expert to disseminate the latest research. After all, expertise from land-grant colleges or research from experiment stations had a long way to travel to improve a farmer’s crop or herd. The Smith-Lever Act made that New York model into a national one, establishing the cooperative agricultural extension network through the USDA and the land-grant colleges focused on both agriculture and home economics.

Supported by both state and federal funds, “cooperative agricultural extension work shall consist of the giving of instruction and practical demonstrations in agriculture and home economics to persons not attending or resident in said colleges in the several communities, and imparting to such persons information on said subjects through field demonstrations, publications, and otherwise,” according to the legislation.

The programs often helped; the farmers often were skeptical – another dynamic with a long history.

Samples

The University of Idaho, where I worked for two decades, collected many of its publications, which you can view through the link below:

Deep Foundations

These examples represent only a sampling of federal programs that have supported agriculture. Other economic sectors enjoyed their own cooperative arrangements for research and practical assistance. (In fact, I’m working on an essay about experimental forests, which follow a similar logic as the agricultural experiment stations.)

At a time of volatility and antipathy toward federal programs as a matter of course, it seemed like a good time to think also about cooperation ahead of regulation and the use of resources designed to support, not stymie, economic activity. These were not perfect efforts, of course; they were instituted by humans within political institutions, after all, and values and priorities change. Still, thoughtlessly undermining such foundations is likely to unearth deep unforeseen consequences.

Comments ()