Standing against Racism in Wartime

How Rupert Trimmingham inspired democracy's best

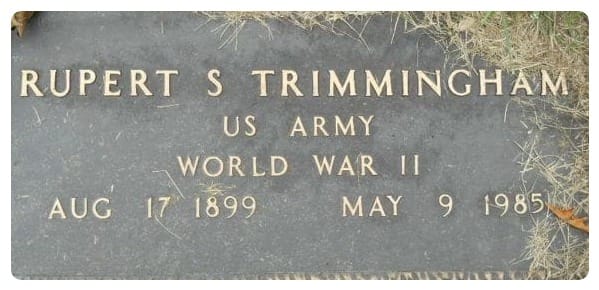

In spring 1944, Corporal Rupert Trimmingham left Camp Claiborne in Louisiana on his way to Fort Huachuca in Arizona. World War II continued in its fifth year, the third with American soldiers in the fight.

The stakes of the war were obvious to everyone with clear sight: democracy or fascism. But racism clouded some Americans' vision.

An Inciting Incident

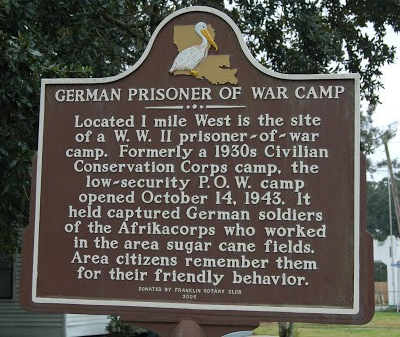

As the trip began, Trimmingham and the other soldiers he traveled with stopped for a layover between trains. Still in Louisiana, the soldiers tried to buy a cup of coffee in local lunchrooms but found them all closed to them. They found one finally at the railroad station, but they had to drink it in the kitchen.

"Old Man Jim Crow rules," explained Trimmingham.

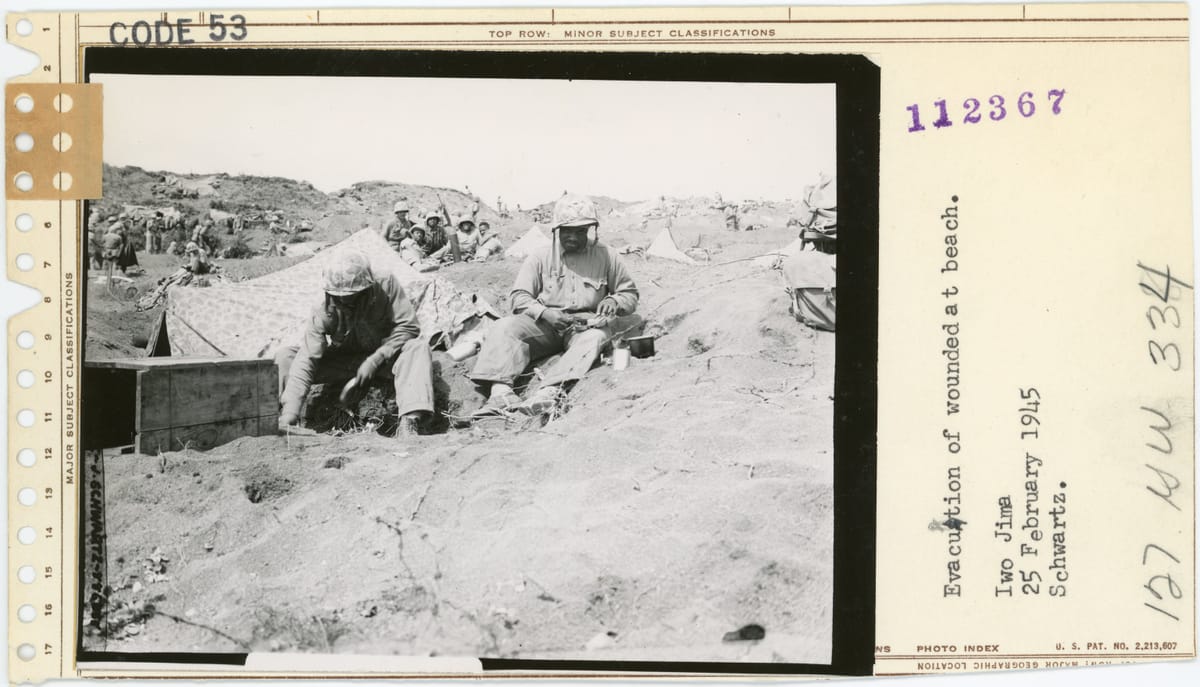

It got worse. While Trimmingham and eight other soldiers attended to their morning coffee in the kitchen, two dozen German prisoners of war arrived at the station and made themselves comfortable in the lunchroom. From what Trimmingham could tell, the Nazi soldiers "had quite a swell time" being served. These captured enemies talked, and smoked freely at the lunchroom tables, while the Black American soldiers were "outside looking on."

To Fort Huachuca

Trimmingham had time to think about the contrast in treatment during his long train ride from Louisiana to southern Arizona. His anger simmered like the desert sun hitting the Huachuca Mountains.

Fort Huachuca long held a place in African American military history, so Trimmingham and his fellow soldiers were arriving in a place with its own Black history. The so-called Buffalo Soldiers were stationed there in the late 19th century, keeping with the practice of assigning Black soldiers to remote posts. At the height of WWII, Fort Huachuca contained the largest concentration of Black soldiers in the nation, some 14,000 troops including WAACs, members of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps.

Fort Huachuca included the first hospital fully run by African Americans. Other similar firsts occurred there, too. Something to take pride in perhaps, but as the writer Lauret Savoy points out in Trace: Memory, History, Race, and the American Landscape, those firsts "resulted from the military's policies of segregation magnified." Such practices produced protests and perverted the war effort, such as when the Army had to draft white nurses while eager nurses remained underutilized at Fort Huachuca, including Savoy's mother.

Soldiers cheering during a show put on by the Hollywood Victory Committee; Captain C.E. Jamison administering anesthesia; an officers' meeting; and WAACs preparing dinner in new kitchen. All at Fort Huachuca, 1942, National Archives.

Some Americans did not recognize the expertise accruing at Fort Huachuca. Eighteen months or so before Trimmingham arrived in southern Arizona, the state's governor worried about a worker shortage for the state's cotton harvest and looked to the Army for help. "I am sure there are many thousands of experienced cotton pickers at Huachuca," said Governor Sidney Osborn, "and I am sure that they could be put at nothing more necessary, essential or vital at this particular moment than aiding in the harvesting of this crop."

Writing to Yank

Perhaps it was such attitudes, or the long train ride, or the fact that Trimmingham was already in his 40s and running out of patience, but after arriving in Arizona, he could not put the incident in Louisiana behind him.

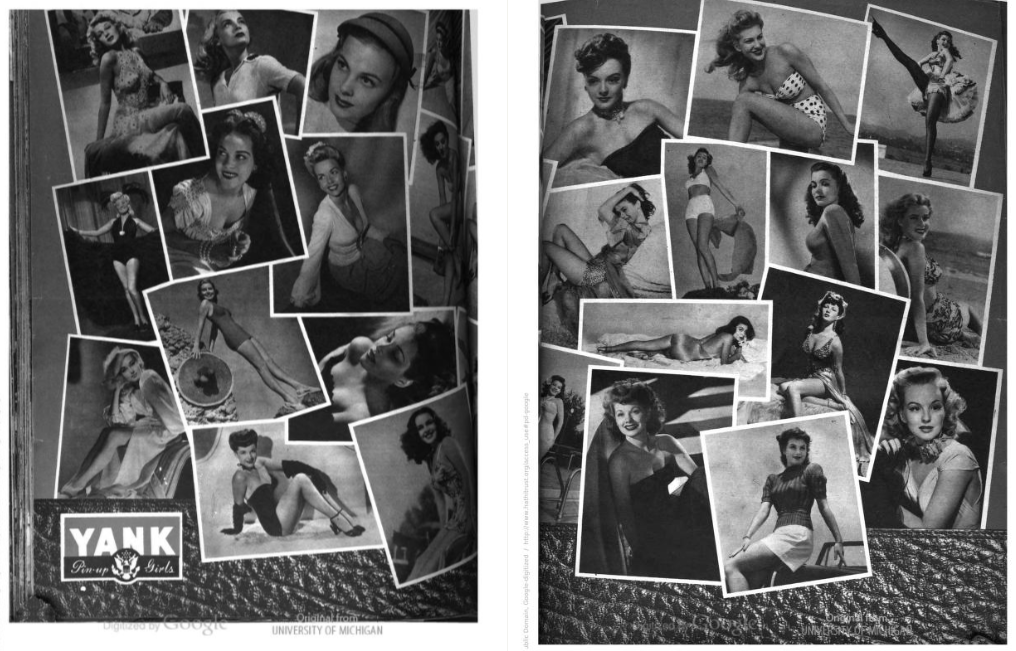

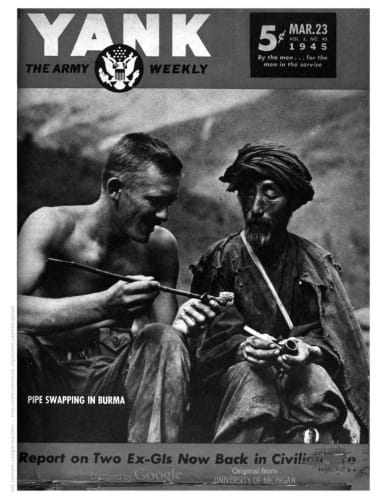

Trimmingham wrote to Yank, the Army Weekly, a magazine that reached 2.5 million people and famously included pin-up photos every week. He posed some questions. To start with: "What is the Negro soldier fighting for?" After describing the shabby experience, Trimmingham wondered why the enemies of democracy were being treated well while soldiers of democracy were being treated like cattle.

"If we are fighting for the same thing, if we are to die for our country, then why does the Government allow such things to go on?" asked Trimmingham.

Responses

Trimmingham sent the letter not knowing if Yank would print it. Not only did it appear, but it generated a strong response that Trimmingham could not have predicted.

Over the next three months, Trimmingham received letter after letter expressing support. By late July, he reported 287 letters, 183 of which were written by white men and women serving in the military. If any were hostile, Trimmingham didn't acknowledge it. Instead, what poured forth was support.

Yank received its own share of encouraging letters. A self-described "Southern rebel" felt disgrace at what Trimmingham and his comrades faced in Louisiana, pointing out that by putting racial discrimination on display for the "Aryan supermen," the locals in Louisiana undermined democracy's war effort.

Another wrote in to acknowledge that racism was "an old wound," a "festering sore," that needed to be cut out of the body politic. Without that, he wondered, "why, then, are we in uniform?"

A group of soldiers fighting in Burma shared their pride at the Black soldiers they fought with in the Pacific. "While we are away from home doing our part to help win the war," they wrote, "some people back home are knocking down everything that we are fighting for." They shared their shame that Americans had treated German prisoners better than American soldiers. Then, they asked a question of their own as an answer to Trimmingham: "If this sort of thing continues, we the white soldiers will begin to wonder: What are we fighting for?" They signed off adding their immigrant ethnicity after their names (Italian, French, Swedish, Irish).

To Be an American

As it happened, Trimmingham also was an immigrant. Born in Trinidad, he immigrated to Wales in the middle of World War I and then to the United States in 1925. He served for the United States in WWII before finally becoming a US citizen in 1950.

But Trimmingham understood what it meant to be an American long before that.

This is true for countless people whose entry into the historical record remains anonymous, small, or posted in corners easy to overlook. But spend enough time reading old magazines and newspapers, talking to family members and respected elders, and you will find the embodiment of civic virtue standing against prevailing prejudices throughout all of American history.

Look quick, though, before the historical record is erased and more books are pulled off the shelves.

Comments ()