Rejecting the Black Silence of Fear

Justice William O. Douglas and freedom of thought and speech

I started writing this week’s essay about national parks when current events pulled at my attention toward former Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas (1898-1980). I’ll get back to the parks next week . . . maybe.

I have written more about Justice Douglas than any other individual, but I have always done so in a slightly peculiar way. Justice Douglas’ historical importance rests mainly on his service on the Court as the longest sitting justice in history. However, in all my writing about him — a book, a book chapter (including a reprint), a magazine article, three journal articles, three encyclopedia entries, and numerous cameos in lots of other work — I typically glance over his legal life and focus instead on his environmental writing and politics.

However, Douglas speaks to our time now in legal, political, and moral ways, so I have found myself drawn to a part of his record I have always overlooked.

Background

Douglas grew up in Yakima, Washington, in modest circumstances. Brilliant, energetic, and ambitious, he launched from the Northwest to make a career first as a law professor and then in government appointments at the Securities and Exchange Commission.

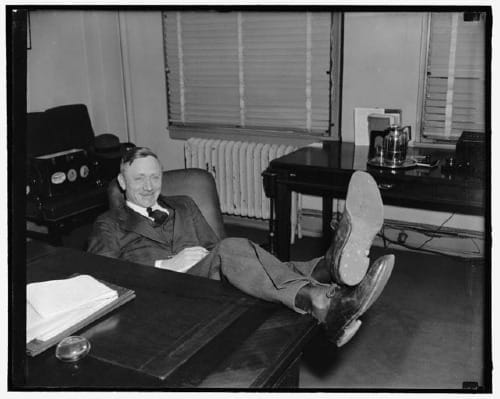

President Franklin D. Roosevelt appointed him to the Supreme Court in 1939 where he stayed until he retired in 1975. By then, Douglas held the record of the most majority opinions and most dissenting opinions written. (Despite this seeming to be a straightforward statistic, it is hard to find definitive data on whether these records stand.)

Something of an iconoclast, Douglas took controversial opinions and lived an unconventional life, traveling the globe during summer recesses, writing dozens of popular books, and taking up conservation causes. Although today he is not remembered widely, Douglas was a prominent public figure during his time on the Court whose ideas and activities made him a household name.

Justice Douglas appearing on "What's My Line" in 1956, showing one of the ways he was well-known in his time. (The first 8 minutes is his appearance)

Arguably nowhere was he more noteworthy — or controversial — than during the anticommunist fervor of the late 1940s and early 1950s.

Douglas in a Stifling Era

Too few people today thoroughly understand and condemn the abridgment of constitutional rights that Americans accepted during the Red Scare of the early Cold War. It is a low point in American history that we have collectively underestimated.

With flimsy evidence and mere innuendo, businesses, schools and governments ran out suspected "communists" — an accusation that covered all manner of imagined (or real) sins almost entirely unrelated to real national security. It ruined peoples’ careers, friendships, and reputations.

This persecution also enforced an orthodoxy on how Americans thought. In 1952, Justice Douglas took to the pages of the New York Times Magazine to rail against this orthodoxy in "The Black Silence of Fear."

Orthodoxy, Douglas argued, suppressed new ideas. A democracy "wants the fullest and freest discussion, within peaceful limits, of all public issues." Instead, as he saw it, the United States had entered an intolerant period. Free speech was "being forsaken for the philosophy of fear through repression."

That fear was overblown: "The Communist threat inside the country has been magnified and exalted far beyond its realities. Irresponsible talk by irresponsible people has fanned the flames of fear." This irresponsible promotion of fear made people afraid to challenge ideas, express opposition, or even support others.

This blanket of fear infected all walks of life. "This fear has even entered universities, great citadels of our spiritual strength, and corrupted them," Douglas wrote. "We have the spectacle of university officials lending themselves to one of the worst witch hunts we have seen since early days." This referenced not only professors being fired for their ideas but also the restriction of topics taught.

Douglas said that young people serve to challenge ideas and prejudices, forcing every generation to reflect on itself. None of that can happen by enforcing a narrow range of ideas and excluding all others by force of law or public pressure — or threat of deportation. The great danger of his time, Douglas believed, was limiting "the range of permissible discussion and permissible thought."

Acquiescing to this fear, Americans were surrendering their power. This was the opposite of freedom and ran against the best ideals of the nation:

If we are true to our traditions, if we are tolerant of a whole market place of ideas, we will always be strong. Our weakness grows when we become intolerant of opposing ideas, depart from our standards of civil liberties, and borrow the policeman’s philosophy from the enemy we detest.

Douglas’ essay was one of his most eloquent statements along these lines, and it followed from his experience on the Court.

A Cold War Dissenter

Douglas and Justice Hugo Black established reputations as consistent defenders of the First Amendment during the early Cold War. Both justices saw the First Amendment in absolutist terms. They did not always reason the same way, but frequently, Douglas and Black ended up on the same side of issues, typically dissenting over these matters.

Congress had passed several laws that criminalized various associations with communism. The most notorious, the Smith Act (1940), outlawed advocating for the violent overthrow of the government or belonging to groups that promoted such ideas, which included communists. No action was required; merely association with unpopular ideas.

In Dennis v. United States (1951), the Court upheld Dennis’ conviction under the Smith Act and argued that the government could limit free speech regardless of whether there was a clear and present danger, which had been the test the Court .

Douglas dissented.

In Dennis, Douglas pointed out that those who had been arrested had been so simply for forming a group to teach communist ideas, namely a handful of books. You could not outlaw the books or teaching them, but you could effectively outlaw the teacher.

"We deal here with speech alone, not with speech plus acts of sabotage or unlawful conduct," Douglas wrote in his dissent. "Not a single seditious act is charged in the indictment."

He continued to assert the preeminent value of the First Amendment:

Free speech has occupied an exalted position because of the high service it has given our society. Its protection is essential to the very existence of a democracy. The airing of ideas releases pressures which otherwise might become destructive. When ideas compete in the market for acceptance, full and free discussion exposes the false, and they gain few adherents. Full and free discussion even of ideas we hate encourages the testing of our own prejudices and preconceptions. Full and free discussion keeps a society from becoming stagnant and unprepared for the stresses and strains that work to tear all civilizations apart. . . . We have deemed it more costly to liberty to suppress a despised minority than to let them vent their spleen. We have above all else feared the political censor. We have wanted a land where our people can be exposed to all the diverse creeds and cultures of the world.

The First Amendment included no exceptions. "Congress shall make no law…" did not mean "Congress shall make no law except against unpopular ideas or those opposed to the party in power."

Ongoing Crises, Consistent Solution

When the 1960s came and anticommunism was no longer the oppressive force it had been, Douglas remained a champion of dissent, then in the context of 1960s protest. He opened his 1970 slender book Points of Rebellion by saying "The First Amendment creates a sanctuary around the citizen’s beliefs. His ideas, his conscience, his convictions are his own concern, not the government’s."

This remains the case; ideological tests have no place in this nation.

Every week, the media shares more and more examples of Americans falling short here. For example, the collective meltdown over "DEI" with the associated penalties imposed and threatened by the current administration demonstrates businesses, schools, and governments will willingly create a Black Silence of Fear again.

In his essay, Douglas wrote,

A strong society is one that sanctions and encourages freedom of thought and expression. When there is that freedom, a nation has resiliency and adaptability. When freedom of expression is supreme, a nation will keep its balance and stability.

We are becoming an unbalanced and unstable nation, teetering on a faulty foundation based on adherence to a narrow range of acceptable beliefs aligned with a madman’s whims.

To be a great nation, to exercise citizenship at its highest level, is to reject the black silence of fear.

Further Reading

- My article about Douglas's best known environmental dissent:

- My latest local story:

- On Saturday, March 15, my monthly interview for paid subscribers will appear. This month, I'm trying a new format that I hope you'll enjoy. If you want access, be sure to sign up.

Comments ()