Olympic National Park's Canonical History

How one park reveals many historical themes

Every national park contains a unique history, but patterns are common across many of them.

If you only had time to learn the history of one park, Olympic National Park might be a good choice to encounter the kinds of opportunities and controversies that illustrate the entire park system.

Creating, then Shrinking, a National Monument

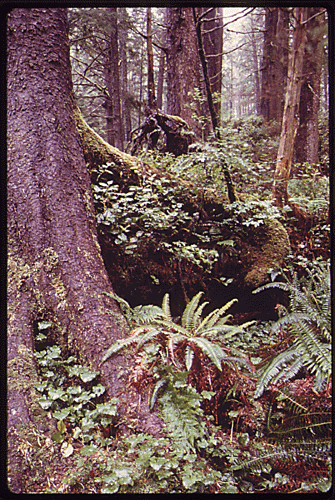

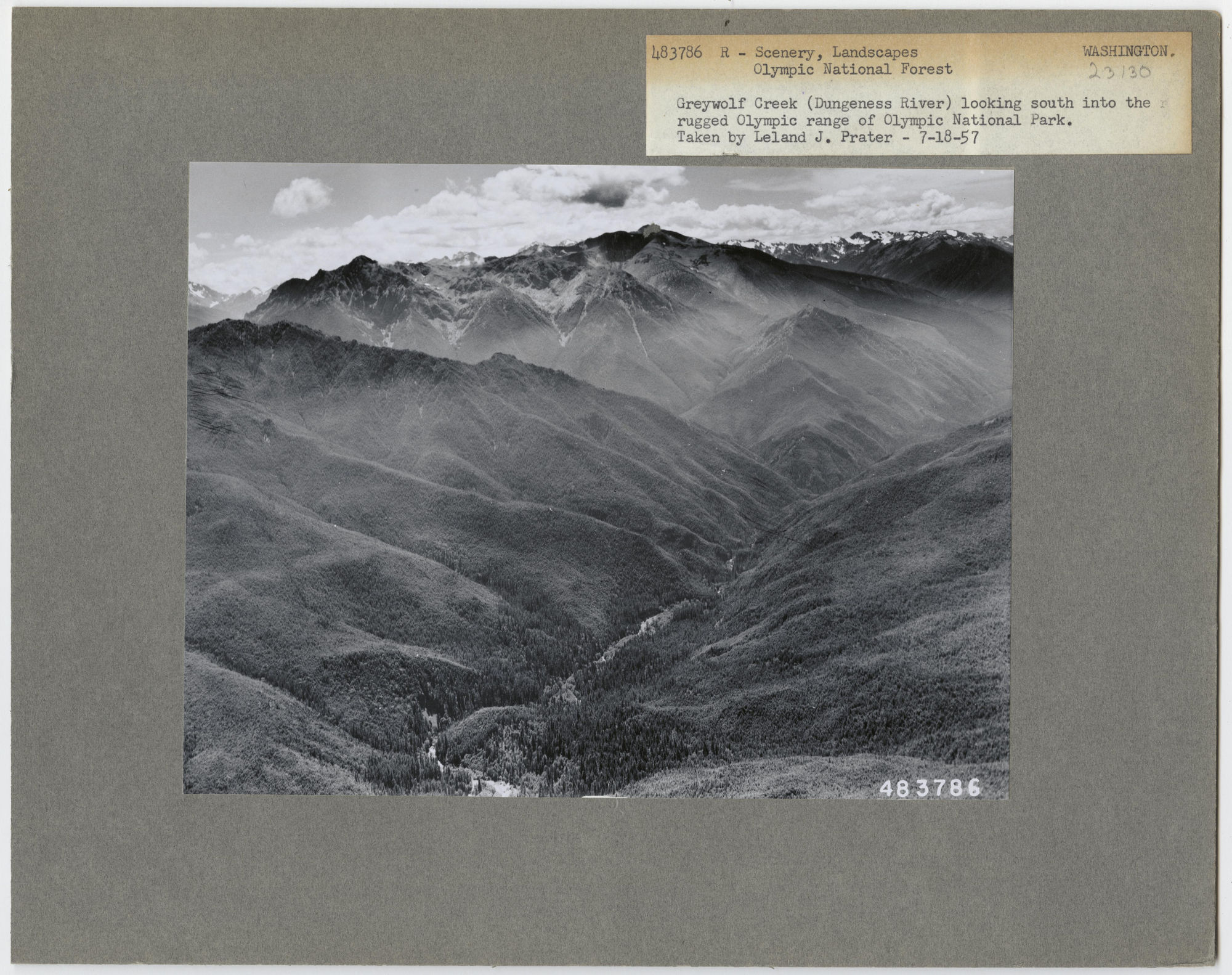

Mountains form the heart of the Olympic Peninsula, and surrounding that core are thick forests of Douglas fir, western hemlock, Sitka spruce, and more. Rivers pour off the mountain glaciers and radiate through a rough landscape before pouring into saltwater on the peninsula’s eastern, northern, and western edges.

The peninsula is a rich land and home to many canonical conservation moments, the type of activity found across the nation's conserved landscapes.

In 1897, President Grover Cleveland protected more than two million acres in the Olympic Forest Reserve. That same year C. Hart Merriam named an elk subspecies that lived there after his friend, Theodore Roosevelt.

By 1904, after Roosevelt had become president, ideas circulated that would have created an Elk National Park to protect the Roosevelt elk from hunters who were killing them for their teeth to be used in jewelry for the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks.

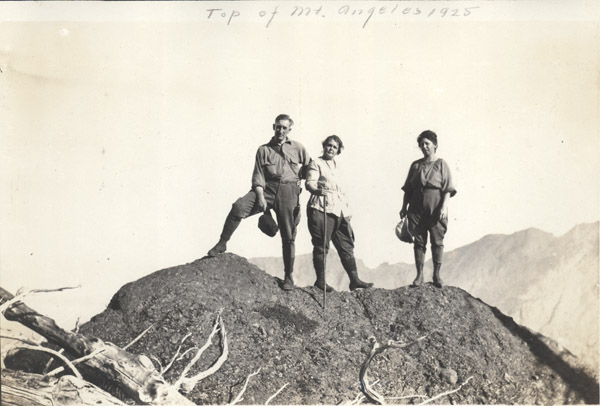

Congress proved uninterested, but President Roosevelt liked the idea of protecting this landscape. And he wanted to pursue it, “without confronting the dimwitted legislators whose insatiable craving for profit blinded them to the inspirational value of geological landmarks,” according to Douglas Brinkley in The Wilderness Warrior: Theodore Roosevelt and the Crusade for America. The geology interested Roosevelt; he wanted to climb Mount Olympus. But Roosevelt also wanted to protect the namesake elk.

With Congress indifferent, Roosevelt turned to the Antiquities Act, which empowered presidents to bypass the legislature to set aside “objects of historic of scientific interest . . . the limits of which in all cases shall be confined to the smallest area compatible with the proper care and management of the objects to be protected.”

The 615,000 acres Roosevelt preserved as Mount Olympus National Monument stretched the “smallest area compatible” criteria beyond recognition according to his critics — something other presidents have also faced, which makes the Antiquities Act a controversial tool for conservation. But Roosevelt was leaving office the next day — a “going-away present to himself,” as historian Hal Rothman put it — and he was not shy in asserting power for conservation.

The national monument would not stay that size.

In 1915, President Woodrow Wilson cut Mount Olympus National Monument roughly in half. World War I had broken out, and manganese was a critical component in armaments. Wilson had been told the Olympics included manganese and reducing the national monument’s boundaries would free it up to be used to support the war effort.

However, not much manganese was ever found. Instead, the portions of the monument Wilson eliminated included large trees the peninsula’s millowners eyed covetously. The timber industry, it seemed, enjoyed greater power than the first Roosevelt president.

A New Kind of Park

The second Roosevelt president curtailed timber’s power . . . at least a little.

In 1933, as part of as larger government reorganization, President Franklin Roosevelt transferred the national monument from US Forest Service management to the National Park Service. Meanwhile, advocates for a park mobilized and attracted his attention.

Key to this effort was the Emergency Conservation Committee, headed by Rosalie Edge and powered by Irving Brant. They envisioned a national park on the peninsula that protected not only the mountains and glaciers above timberline but also the rain forests on the western edge. As they mobilized to transform the monument to a park, the debate focused on what the boundaries would contain.

In 1937, Roosevelt toured the peninsula. Arriving in Port Angeles, he saw a banner attached to a school:

Mr. President, we children need your help. Give us Olympic National Park.

When Roosevelt spoke there, he emphasized how the park would benefit children more than adults since they were the future for which conservation was intended.

That evening at Lake Crescent Tavern (now Lodge) Roosevelt consulted others about boundaries and the thorny issues involved. The next day, he continued a counterclockwise trip around the peninsula, this time in the hands of the Forest Service and timber interests, who opposed a large park that would envelop more of the Olympic forests into a protected category.

These handlers tried to keep Roosevelt from seeing damage local logging caused, even going so far as removing national forest boundary signs so it appeared that clearcuts were on private, not federal, land. However, anyone who has traveled through timber country knows that you can only hide clearcuts so long.

At one site where the debris from recent logging was most ugly, Roosevelt remarked:

I hope the son-of-a-bitch who logged that is roasting in hell.

The park advocates had won.

In 1938, Congress passed legislation creating Olympic National Park at some 648,000 acres. But Congress had not been able to resolve all the boundary issues and granted the president the power to add more land after consulting others about the matter — a rather extraordinary grant of power since “consultation” did not mean “compromise.” In 1940, Roosevelt added another 187,000 acres.

From the start, park supporters wanted Olympic National Park to remain largely wilderness. Many national parks accommodated visitors with roads, hotels, and other developments. Olympic would instead build minimal roads and visitor infrastructure to preserve the wilderness character.

Secretary of the Interior Harold Ickes championed this vision effectively, perhaps a surprise for a man who cut his teeth in Chicago politics. In a speech, Ickes spoke eloquently:

Limit the roads. Make the trails safe but not too easy, and you will preserve the beauty of the parks for untold generations. Yield to the thoughtless demand for easy travel, and in time the few wilderness areas that are left to us will be nothing but the back yards of filling stations.

Ickes captured a key component of the emerging wilderness movement that was coalescing around the need to limit automobiles penetrating the American backcountry.

Logging the Park

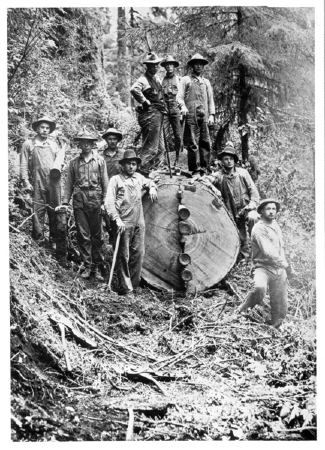

No doubt the powerful timber interests on the Olympic Peninsula found park politics disconcerting as logging was not allowed in national parks. However, millowners found a National Park Service willing to work creatively around the edges of rules.

National park legislation allowed the agency to permit logging if it could prevent insect infestation or windfall. The NPS needed merely to decide that a block of trees might blow down or be susceptible to infestation.

Ownership patterns meant sections of private land could be interspersed with the park boundaries. A logging company could clearcut its section, thereby increasing the risk that windstorms would topple adjacent trees, thus justifying more cutting to prevent that. At times, the company then exchanged the cutover land for timbered federal land elsewhere.

This process was somewhat self-perpetuating and certainly at odds with the intent of park legislation.

However, Fred Overly, a NPS ranger, had worked before as a logging engineer. He happily accommodated his former boss’ requests for park trees. Another ranger, Preston Macy, readily traded timbered land for logged off land.

This process began in 1941, when the war effort seemed to justify many exceptions to conservation. But the program kept growing. By the end of 1948, nearly 11 million board feet had been cut from the park. In 1952, Overly allowed 7.3 million board feet; the next year, that number doubled. When the public finally caught wind of this and rallied to stop it in 1958, the Olympic National Park had been stripped of about 100 million board feet.

New Legacies

The subsequent story of the park includes many other notable moments (and controversies). Many of these also connect to common conservation problems (e.g., removing introduced species). Perhaps I'll revisit some of these stories, but I want to end with some hope.

Local tribes, especially the Lower Elwha Klallam Tribe, and environmental groups advocated for decades to remove two dams along the Elwha River within the park, which had blocked fish runs for a century. Authorized in 1992, dam breaching took two more decades to happen, thanks to political opposition and the technical challenges.

Almost immediately, salmon and steelhead recolonized the Elwha and its tributaries. The ongoing restoration project, a partnership effort, is producing more fish and a healthier ecosystem, as well as increasing our knowledge about ecology and repair. The Elwha restoration adds a profound component to Olympic National Park's history.

Throughout their histories, national parks have been hailed as living laboratories. And since the 1960s, restoration has been a key part of the agency's focus. Repair, thus, sits alongside preservation.

In Other Words

- Last week, a local newspaper got started. La Conner Community News has been published online for a few months now, but its first print edition appeared last Thursday, and I was proud to have a story in it. That story looks at what the very first newspaper published in that town — in 1879 — revealed. You can read it here.

Comments ()