Dissenting from within Federal Agencies

The origins of the Association of Forest Service Employees for Environmental Ethics

The federal land agencies have been hit hard in 2025 by layoffs, hiring freezes, and leadership instability. Public reaction has been strong, especially in the West where such agencies have a large presence, because westerners across party lines want land and resources protected.

In other words, the grassroots are dissenting from the policies being carried out.

The avenues to express that dissent are easy for a member of the public. But speaking out from within the agencies carries risks. When it occurs, it reflects evidence of significant turmoil. The conditions that produce dissent and that facilitate its sharing have an interesting and important history in the Forest Service.

The Catalyst of Change

Jeff DeBonis tried to be a good employee for the Forest Service, but by 1989 he had reached a limit.

DeBonis had started on the Kootenai National Forest in Montana, then went to the Nez Perce National Forest in Idaho, before ending up at the Willamette National Forest in western Oregon. Before that, he’d worked in the Peace Corps in El Salvador and for USAID in Ecuador where he had seen terrible damage caused by deforestation.

In the Forest Service, DeBonis encountered people who shared his concerns, but the culture at large tilted toward clearcutting old-growth forests. A 1990 story in American Forests quoted DeBonis saying of the agency, “We were set up to produce timber outputs. The system rewarded those who met board-foot production targets.”

By this time in Forest Service history, environmental values were supposed to be incorporated into forest planning. But as a timber sale planner, DeBonis had concluded that his work amounted to, “getting a lot of data to justify timber cutting,” according to William Dietrich’s reporting in The Final Forest: The Battle for the Last Great Trees of the Pacific Northwest (1992).

Increasingly, the agency ignored its own scientists (something I wrote about here).

DeBonis wrote a letter to the Forest Service chief, Dale Robertson, stating the agency's policies could not be justified. It is one thing to privately tell your boss you disagree, but DeBonis sent his letter publicly on the agency’s system-wide early email system. The act was “a career-limiting action,” in the understated words of sympathetic forester Jim Furnish in his memoir Toward a Natural Forest: The Forest Service in Transition (2015).

DeBonis then formed the Association of Forest Service Employees for Environmental Ethics (AFSEE). He started publishing Inner Voice, a newsletter that helped organize like-minded employees and provided a forum to discuss forestry reforms, known then as New Perspectives or New Forestry.

AFSEEE demonstrated widespread dissatisfaction within the Forest Service and helped hasten moves toward reform.

How had this moment arrived?

Planting Seeds

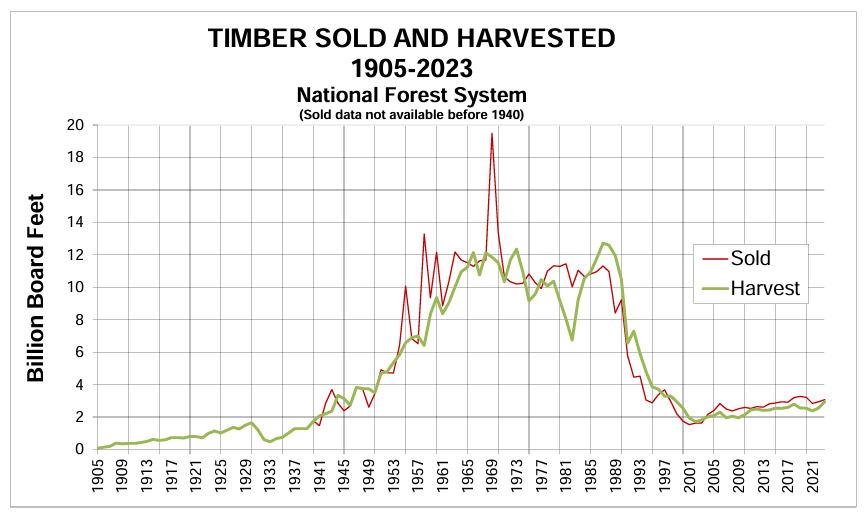

The story that often prevails in popular understanding is that the federal government instituted severe environmental restrictions on national forests by laws passed in the 1960s and 1970s. Legislation such as the Wilderness Act (1964), National Environmental Policy Act (1970), and Endangered Species Act (1973), did impose some restrictions and generated a brief decline in timber sales.

However, timber cutting continued and, in fact, increased significantly in the 1980s.

Meanwhile, scientists uncovered significant environmental harms — to animal populations, water quality, and the like — caused by existing cutting practices and intensities.

The National Forest Management Act (1976) reduced clearcutting, required viable populations be maintained for vertebrate species, and demanded a rigorous planning process on each national forest – a process that required interdisciplinary teams. Together, these mandates forced the Forest Service to develop a different set of expertise, the -ologists (e.g., biologists, hydrologists, etc.).

These scientists looked at the forest differently and possessed different management tools from the traditional foresters, the so-called timber beasts, who seemed to only have chainsaws and timber sales in their management toolbox.

Another way of putting it: adding diversity to the workforce produced new ways of understanding the agency’s task.

Although none of the accounts of AFSEEE’s origins explicitly mention this, DeBonis worked on the same ranger district as the H. J. Andrews Experimental Forest (which I’ve written about here). Surely the experiments and rethinking that originated there about the value of old-growth forests influenced DeBonis and added depth to his challenge to the agency.

By the late 1980s and early 1990s, the gap between protective legislation and actual management, as well as the difference growing between scientific knowledge and status quo on cutting levels, became too great. The breaking point that DeBonis and AFSEEE represented was felt widely.

The Right – and Need – to Dissent

DeBonis decided to quit by 1990 to work on AFSEEE full time. By 1992, he helped form Public Employees for Environmental Responsibility (PEER). That such organizations had to be created in the George H. W. Bush administration and have continued to be used shows the continued need to organize and advise federal workers of their rights.

Short video of Jeff DeBonis sharing his story.

I see their establishment as an important historical moment that reflected the integrity of employees seeking to work ethically within a system often bent by perverse incentives, political manipulation, and entrenched practices.

The forms of resistance have evolved. Consider the Alt National Park Service which has maintained a lively, resistance-focused social media feed since 2017 that is followed by hundreds of thousands.

In that 1990 American Forests article about DeBonis, he was called a “folk hero of Forest Service dissent.” To dissent is difficult in any institution or time; doing so is easier with support. FSEEE (the “association” has been dropped from its name) and PEER have published guides about free speech and reporting abuse safely to help employees feel freer to dissent.

I imagine we will be hearing more dissension from the ranks, as dedicated public servants seek to protect America's federal lands for the future.

Comments ()