After Earth Day

Standing for nature every day

We are all living after Earth Day, literally and figuratively.

Today is the day after the annual day of picking up trash and remembering to recycle, perhaps also planting a tree. These are all good things, and I do not mean to disparage them entirely as trite or meaningless. But most of the time Earth Day leaves me a bit cold, because I imagine that improving our relationship with the planet requires a different approach or that the day might be something else.

1970

“I suspect that the politicians and business men who are jumping on the environmental bandwagon don’t have the slightest idea what they are getting into,” said Denis Hayes in his speech, “The Beginning,” on the first Earth Day.

Hayes was the lead organizer for the nationwide event. He spoke in the nation’s capital and saw the potential for something revolutionary, because he understood the full-scale harm being done to the environment.

“We are systematically destroying our land, our streams, and our seas,” he said. “We foul our air, deaden our senses, and pollute our bodies. And it’s getting worse.”

If these things were true, they demanded action.

The first Earth Day originated as a teach-in, the brainchild of Wisconsin senator Gaylord Nelson. Earth Day was meant as an opportunity for local communities to become better educated about the natural world around them and the threats to it. Its mostly decentralized nature meant grassroots concerns bubbled up and radicalism was kept at bay.

Something like 20 million Americans showed up that first Earth Day, a number that represented 10 percent of the nation. It was the largest demonstration in history and is often credited with much of the political transformation that occurred in the 1970s, including new institutions and laws like the Environmental Protection Agency and the Endangered Species Act.

These and other developments pointed toward new political relationships with nature. And environmental conditions improved because of these laws, as shown by the Documerica photographs highlighted here.

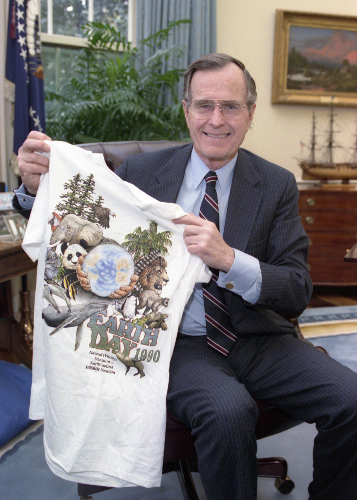

1990

But when the 20th anniversary of Earth Day came around, a rejuvenation was needed.

An environmental backlash during the Reagan years threatened to undermine any gains. Besides, scientists and activists pointed to the global problems that demanded attention. Joining neighbors to clean up the neighborhood park could feel insufficient.

Preparations for the anniversary followed a different path but still attracted wide attention.

In New York City’s Central Park, almost a quarter million came to celebrate. In historian Hal Rothman’s sardonic words in The Greening of a Nation?:

Together they created almost forty-five tons of refuse; it is entirely possible that the planet might have been better off if they had just stayed home.

This metaphorical pile of trash symbolized too much of the 1990 Earth Day. Corporate sponsors had hopped on board, showing support but also emphasizing individuals’ responsibility to fix the earth. No need for stricter regulations or economic reform, just recycle and ride your bike.

At the same time, environmental organizations had become bigger and more sophisticated with growing budgets and staffs. Consequently, the 1990 anniversary became more of a top-down affair.

As environmental historian Adam Rome contrasted 1970 and 1990, the organizers aimed to enlist people into the movement rather than empower them to act according to their own ideas and community.

Success forces evolution, for better or worse, and change continues.

Evolving Celebrations

Earth Day keeps evolving, and doing so, it reflects the concerns of its context. By the 2010s, actions associated with climate joined Earth Day events.

And while our air and water are cleaner and better regulated than on April 22, 1970, assaults on environmental protection in law and the relentless hostility toward any action on climate by the Republican Party can all make it easy to sigh in frustration.

Earth Day is not to blame, of course.

Hayes ended his inaugural Earth Day speech by noting that “Earth Day is the beginning.”

The problem with many Earth Day celebrations is that they are the beginning and the end, a circled day on the calendar rather than a yearlong commitment. I often think special days that draw attention to a cause allow us to forget about it on the other 364 days.

2025

Yesterday, I wished my wife a Happy Earth Day. She parried back my lack of enthusiasm with a bit of a grumble. Then she perked up a bit and said, “We stand for what we stand on.” I could tell she was reciting some sort of slogan. She told me the campus environmental club she joined included that line on a t-shirt.

I investigated to discover it comes from the final line of Wendell Berry’s poem, “Below.” It’s a lovely short poem that shows how so much points our attention above — treetops, crosses, stars — but Berry aspires downward, he says.

All my dawns cross the horizon

and rise, from underfoot.

What I stand for

is what I stand on.

We stand on the earth every day, not just on April 22. To stand for it requires us to remember that every day and act as though it were true. Nothing is truer, after all.

Comments ()